12 Sep What the First World War teaches us about European integration and disintegration

This was written as an introductory essay for the book “Shaky Ground: Traces of the Great War in the Ypres Salient”, by Peter Dekens.

The idea of European unity, in any case the official entity as it is communicated by the European Commission, is intrinsically linked to the end of the Second World War: the Stunde Null or ‘Hour Zero’ on the 8th of May 1945. Industry was in shambles, many cities had been destroyed, and the European societies had to find a way to make peace with the guilt and shame associated with the Holocaust. The pioneers of European integration in the 1950s all agreed on one thing: Never again. No more war.

It is a powerful and persuasive image. Clean and clear. Very simple, too – almost as simple as the ‘American Dream’. From that point on, the concept of European integration was framed almost naturally in terms of an unwavering contrast between the past and the present. The European (pre-WWII) past was chauvinism, petty disputes, and war, while the European (post-WWII) present was multicultural, cosmopolitan, peaceful, and prosperous.

Simple solutions can be deceiving, however, and this was no exception. The choir of critical politicians, policy-makers and opinion leaders is swelling. These voices, the critics and sceptics, are found on the left and the right, in the East and the West, and are unfettered by post-war taboos: Is Europe actually all that multicultural, peaceful and prosperous? And should it be? Why, or why not?

Cultural critic Ivan Krastev from Bulgaria noted in the introduction to his pamphlet, After Europe, that there are many theories about European integration, but none at all about European disintegration: ‘The architects of the European project have fooled themselves into believing that avoiding mentioning the “D” word is a sure-fire way to prevent it from happening. For them, European integration was like a speed train – never stop and never look back.’

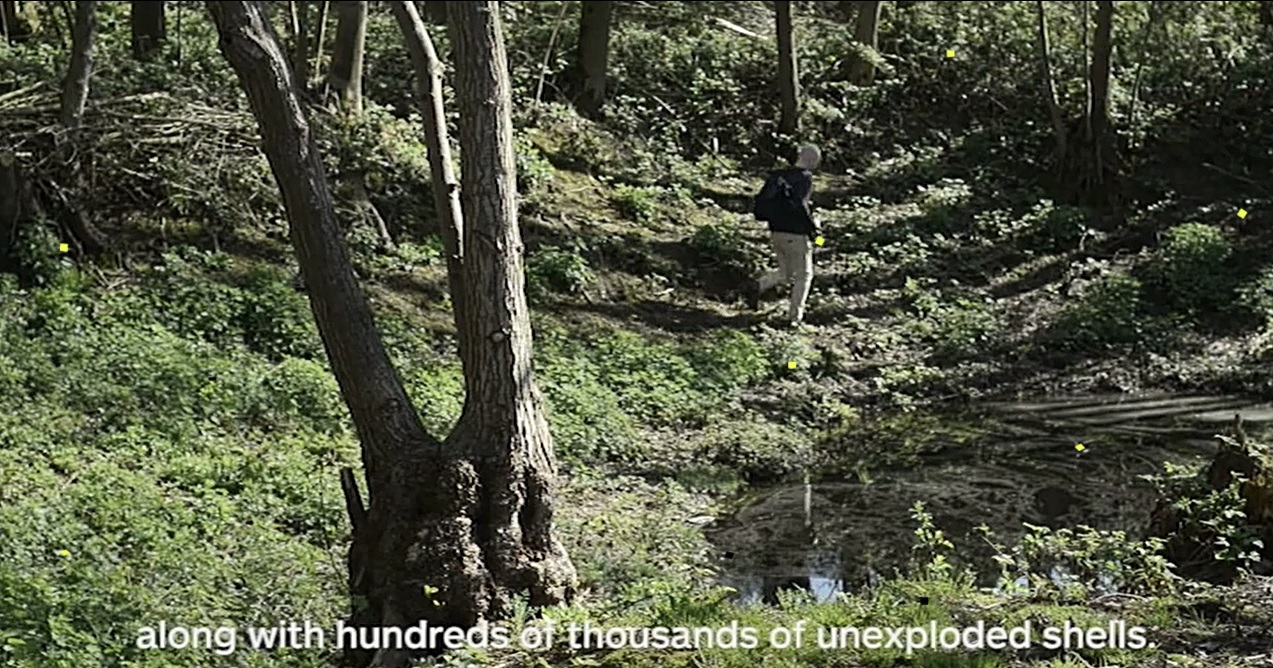

From the Promovideo for the project “Shaky Ground” (Peter Dekens)

Trends and events that are familiar across the continent have cast the time-honoured contrast between the old Europe of war and the new Europe of peace in a new light. Brexit set off alarm bells, of course, but so did the populist revolts in both Western Europe (France, the Netherlands) and in Eastern Europe (Hungary, Poland, Slovakia). Global superpowers are stirring the pot of European unity as well, not least Putin’s Russia and Xi’s China. The automatic faith in that familiar dichotomy has been transformed into gloomy doubt, perhaps even fear. Some European countries, even within the EU, are considering reintroducing the military draft. A majority of the population in three EU member states (Bulgaria, Slovenia, Greece) believe that it is not the European Union that will come to their aid in the event of a disaster, but Russia.

There may not be a solid foundation of theory addressing European disintegration, but there are lessons to be learned from history. Those lessons take us back to the first half of the twentieth century, even before Stunde Null. Around the turn of the century, on the eve of the First World War, Europe was a large, powerful continent made up of many different peoples and nations, where borders were porous and where a network of socially and ethnically diverse urban societies maintained a cultural Belle Epoque. It was also a continent of insecurity, self-aggrandizement, and boastful arrogance. And something was brewing beneath the surface, an undefined unrest. Large-scale modernisation and industrialisation had turned the world inside-out; the cities were filling up with migrants (often from poor outer provinces and underdeveloped rural areas); and miraculous scientific discoveries had given rise to faster transport, more intensive communication, and more efficient production. Minorities and women were claiming rights, wanting to take active part in society.

Not everyone was pleased. So many developments, so many changes: the Europeans were reeling at the pace of it all. Political and social movements emerged, promising to eliminate the confusion, to introduce or restore order. These movements saw the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 as an opportunity. Some soldiers, but above all a number of imaginative intellectuals and megalomaniac emperors believed that the war would put an end to modern confusion and sort Europe out once and for all.

World War One is viewed as a war of nations and nationalists, and that is partly true. However, it was also a European war, in the sense that each party to the conflict believed that their own sense of structure would be beneficial for all of Europe. The cultural clichés of each region fed into that belief. Germany was convinced that the German Kultur, the Romanticism of the Dichter und Denker, the poet-philosopher, would cure the European continent of modern confusion. France believed that Europe was yearning for French Civilisation, for the Enlightenment, for Voltaire, Rousseau, and the sensible voice of French reason. Czarist Russia was fighting for a Slavic-Orthodox Europe replete with profundity, while Great Britain championed a British-Liberal Europe with free trade, and so on and so forth.

In essence, all these major powers wanted to bring order and uniformity to Europe – but according to their own principles of what would be orderly and uniform.

The soldiers on the battlefield were the first to realize that the idealized uniformity was a grotesque illusion. After just a few months, the armies had ground to a terrible halt, facing off across the trenches of Belgium and Northern France. The war fronts in Eastern Europe were more chaotic and dynamic, but even where war was in motion, soldiers had no way of seeing the bigger picture. Nameless foreign soldiers ran towards them, and they mowed them down with machine guns; all that remained was death and destruction. The only thing left standing was the implacable truth of violence. And technological progress had made it possible for violence to be committed faster, more efficiently and more productively than ever before.

The reality of war was devoid of any semblance of uniformity. In December 2014, soldiers even crawled out of the trenches to celebrate Christmas with their opponents. The German, British and French soldiers amicably drank wine and beer together, and shared their chocolate. They played football in no-man’s-land, laughing, singing and cursing, before returning to the trenches to resume their duties: mowing down the enemy.

It is unsurprising that the forests did not survive those battles. Trees get in the way; they block lines of sight, obstruct the bigger picture. The hills of Flanders along the front lines were rapidly transformed into muddy, desolate, lunar landscapes with the occasional tiny sapling or craggy stump here and there. Despite the swampy soil, trees continued to take root. Nature disregards human desires for uniformity. It grows where it will, and lives wherever life is possible. The photos in this book bear witness to nature’s resilience. Mud finds its own path. The trees that were struck by shell-fire kept growing, some of them for decades, silent witnesses to the ravages of war. Only time, shaped in those slowly rising trunks, brought the clarity of the bigger picture to the battlefield.

Just as the Second World War, and the resulting concept of European unity, is anchored in superficial images, the same holds true for what was known as the Great War. It was portrayed as a ‘futile’ war, an ‘endless slaughter’. The cinematic, popularised images of muddy futility are based in part on actual history, but they overlook the complexity of that war. It was neither futile, nor coincidental. Everything can be traced back to a cause.

The First World War does not teach us that ‘evil’ has a face (an assumption which is much easier to make in the context of the Second World War), and can be fought on that basis. On the contrary, the First World War has no face at all, no one person to pin it on, so it demands more from our imaginations. A hundred years later, the Great War teaches us that sudden panic about international confusion, panic sowed by inexpert, clumsy, often unstable and incompetent officials and diplomats can lead to the most awful suffering if it is converted and put into practice in the form of violence. And it teaches us that such violence cannot be taken back or undone. Violence gives rise to violence. And such things give birth to immense trauma that echoes down the generations.

This brings us to the present day. In 2018, many Europeans are confused by their own lives and the world around them. Once again, technological progress has caused fundamental changes to how media works. In 1914, the newspaper was the new medium causing an information revolution and transforming society; in 2018, social media is taking on that role. Throngs of migrants are amassing, primarily in the public eye through the new media that takes up so much of our attention. The final touch: the international balance of power has become multipolar and extraordinarily complex. Who’s the enemy, and who is opposing them? Iran? Saudi Arabia? China? North Korea? Politicians are promising order and uniformity, at home and in the global arena. The solutions available to us are limited: either returning to the nation-state, or moving forward in the European Union.

Both sides, the proponents and opponents of the European Union, could stand to learn from the past. Only the soldiers who fought in the First World War, on the western or eastern front, proved capable of understanding that it was impossible to make Europe ‘German’ or ‘French’, in the broadest sense of the word. They stood face to face with individuals; the people across from them may have been inducted into huge armies, but even so: individuals, armies filled with individuals. The soldiers in WWI saw the trees through the forest, each unique, each different. Just as the Europe of that time could not be stamped into the mould of the German Kultur or the French Civilisation, it would be dangerous to try to fit the European Union of today into either a left-wing liberal or right-wing conservative framework. Those disparate Europes must be able to co-exist side by side, sharing the same philosophical and physical space, in what Dutch political philosopher Luuk van Middelaar has referred to as the ‘Binding Dissensus’. It is not orderly, nor is it remotely uniform, but as long as contrasts are not converted into violence, this confusing Europe can continue to thrive. If there is anything that can be considered characteristically ‘European’, anything that all Europeans should be able to recognise as their own, it is the ability to live amidst pluriformity, multi-faceted diversity, contrasts and paradoxes – to learn to live with confusion.

The photos in this exceptional book clearly show how the First World War brought anything but uniformity, anything but order and peace. On the contrary, they show that war brings with it the realisation, possibly even the comfort, that human emotions are universal… emotions like oppressive terror, desperation and fear.

Peter Dekens: Shaky Ground: Traces of the Great War in the Ypres Salient

Eriskay Connection (Amsterdam), 122 pages, € 35.

Please watch the short video by Peter Dekens about his Photography Project:

My very earliest memory of WWI dates back to 31 May 1979, when I was twelve

I’ve been working for more than two years on this photo project about the remnants that are still present today from the First World War. The project is called ‘Shaky Ground’ and takes place along the frontline around Ypres (The Ypres Salient, Belgium).This book can only be produced with your help! Please consider supporting the crowdfunding and get a copy of the book: www.voordekunst.nl/projecten/7273And many thanks to share this message.Grateful,Peter

Posted by Photobook: Shaky Ground by Peter Dekens on Tuesday, 1 May 2018